The winemaking appellation of Priorat has a special place in my heart and that’s a passion I love to share with wine & food lovers visiting Barcelona.

The beautiful views from charming Gratallops

Located just under two hours from Barcelona, Priorat’s landscape is marked by steep hills and narrow valleys. It’s a dramatic and often harsh land with little vineyards growing on steep inclines or little shelves that have been laboriously cut into the hillside. The soil here is dominated by black and grey slate. A type of soil that makes for a tough life for the vines as their roots have to press their way far down in search of tiny pockets of water that allow for their survival. Most winemakers here don’t irrigate either as they believe the plants should suffer so they get stronger. Only that way will they be able to produce quality grapes for decades to come. And the men and women who work the land have to be prepared to suffer too. You’ll see very little in the way of mechanized farming as the hillsides are simply too steep for them to operate. In Priorat the winemaker’s best friend is the Ruc Català – the race of donkeys native to Catalonia and long appreciated for their sturdiness.

The vineyards of Meritxell Pallejà, growing straight out of the ubiquitous slate-rich soils

The wines here are mainly red and generally made from Carinyena (also known as Samsó) or Garnatxa, often as blends as they complement each other very well. Only about 5% of Priorat wine is white with main varieties being the Garnatxa blanca, Macabeu, Pedro Ximénez, Moscatel de Alejandría and others. Due to the mentioned characteristics of the area, yields are typically low.

As you’ll understand, these kinds of conditions greatly impact the type of wine that ends up on the table. They are wines brimming with character and traditionally need both barrel ageing and several years in the bottle before all the complexity really starts to shine.

Herein, I think, lie the reasons why I love Priorat and its wines so much. It requires tremendous effort from the plants followed by total dedication from the winemaker to achieve a great wine. Maybe the truly worthwhile should never be simple to accomplish.

Are you in Barcelona or going there soon? At Wine Secrets Barcelona I arrange tastings in my beautiful space in the city as well as excursions to places nearby, like the unforgettable Priorat.

Vinyards above the town of Porrera, one of my favorites

Heading to the Spanish Heartland: Toro!

Part 2

After my visit and tasting at Estancia Piedra, I was starving. So I jumped in my rental and headed back into the town of Toro, hoping to find an open restaurant serving up something delicious. What I was really hankering for was to sink my fangs into some of that juicy suckling pig that this part of the country is known for. Unfortunately, it was already four in the afternoon. That dreaded neither-fish-nor-fowl hour when it’s too late for lunch and way too early for dinner. I absolutely refuse to eat just anywhere and the idea that food is simply fuel makes no sense to me. Yet, over the years, I’ve developed something of a sixth sense when it comes to ferreting out good eateries in unknown places. And so it was in this case too.

Mouthwatering Cecina (cow’s ham) and Delicious Homemade Meatballs with the Local Bread

I had lunch in a little hole-in-the-wall eatery that I stumbled upon in the historical center of Toro: Bar Arco del Reloj. It looked promising enough to venture in for a glass of wine so I could scout the wares. As I walked in, I spotted a group of locals playing a card game with the owner at the corner of the counter. It took them about a tenth of a second to spot me as an outsider. This was as authentic as I could hope for! It was abundantly clear that this was their turf and not mine, but more often than not you’re warmly welcomed by the natives if you show some interest in the local wine and food. And I’m always very interested in good local wine and food. The kitchen was still open and I ordered a tester dish of cecina: ham made of beef, typically smoked. It was delicious! I spent the next hour standing at the counter eating spicy little sausages cooked in cider, meatballs and cured Zamorano cheese. A juicy local red wine paired well with the food and I was happy. It was time to get back to wine hunting.

Tranquility Reigns in Toro

Just a 10-minute walk from where I had eaten, and still in the old part of town, lies the cellar of Bodega Bigardo. With only a couple of days’ notice, owner and wine maker Kiko Calvo had agreed to receive me and, although he had warned me that he didn’t have much time that afternoon, we ended up spending the next 2.5 hours visiting vineyards, his cellar and tasting straight from the barrels.

Bigardo is a small winery born from the passion that Kiko feels for his native Toro. He grew up among the old vines that his father cultivated and subsequently worked at other, much bigger wineries in the area. But Kiko wanted something of his own and he wanted to make wines his own way. The symbol that has become his trademark, a fist with the index finger and pinky raised, is not in reference to AC/DC or anything satanic. It symbolizes a bull or toro, the name of his town. Still, I couldn’t help but think that Bigardo is the defiant result of a young man’s desire to break out and do things differently, regardless of what others may think or advise. As Kiko was explaining his approach to wine making and his search for the purest, most unadulterated wine possible, we were standing on a plot of 80-year-old vines, splayed out before us in all of its rustic beauty. Down the sloping hill lays Bodega Numanthia, owned by luxury goods conglomerate LVMH. The contrast could not have been more palpable.

Kiko Calvo of Bodega Bigardo in his Element

If I had to sum up Bodega Bigardo in one word it would have to be “honesty”. Kiko knows full well that he is sitting on a treasure in the form of abundant access to old vineyards that produce the highest quality grapes anyone could ask for. Thesevines grow in the sandy soils that are so typical of this area between Valladolid and Zamora. Beneath the sand, you find marine deposits that give the wines a mineral component, adding richness and texture. To express that balance of fruit and complexity, Kiko’s wine-making philosophy is to intervene as little as possible. He doesn’t use any pesticides, doesn’t filter his wine, crushes and presses the grapes very gently and in combination with whole cluster work. There’s no use of new oak.

An Absolutely Spectacular Day in Beautiful Surroundings

Tasting Straight from the Barrels. Fun and Challenging!

Bigardo is a popular wine and when I was there Kiko didn’t have a single bottle left that we could taste. They had all been sold. So we tasted straight from about ten different barrels of the 2018 harvest. Different types of oak, different coopers (tonneliers), different toasting. One single batch of wine had gone into these different vessels and the wine had subsequently taken on slight variations and tweaks. One barrel had an earthier tone; another, livelier fruit notes and yet another, a more austere, mineral style. Subtle, but distinct differences from one barrel to the next. These nuances give Kiko the palette he can play with in creating the wine he feels most represents his land, his vines and himself.

In just a few weeks I’ll taste these same wines again, but this time the wine will have come together much more and will present itself differently. Wine is, after all, a living thing that never ceases to evolve. That is, until you drink it.

Heading to the Spanish Heartland: Toro!

Recently I spent a day visiting two different winemakers in the area of Toro, a two-and-a-half-hour drive west of Madrid towards the Portuguese border. This town of some 9,000 inhabitants oozes wine history everywhere you go. It’s located on top of a cliff with the Duero river flowing by at its base. Follow the Duero inland and you quickly get to the world-renowned appellation of Ribera del Duero (the “Banks of the Duero”). If you head in the opposite direction, the Duero meanders its way towards Portugal where the river actually marks the border between the two Iberian countries before cutting west and finally spilling into the Atlantic Ocean in Porto, another city with a rich history in wine.

That morning I had gotten out of bed in my Barcelona home at the inhuman hour of 4:45 am! Strictly speaking, no one should subject themselves to such horrors, but hey: I was going wine hunting! Yes, the purpose of my trip was to source wine for two different wine importers, one in Sweden and the other in Norway.

About to Board with my Tool!

As you may or may not know, both Scandinavian countries have government monopolies on the sale of alcoholic beverages to the general public, bars and restaurants aside. One of the ways that these chains of government-run stores supply themselves is by issuing tenders. This way, they announce that they’re looking to buy an estimated number of bottles, or bag-in-box units, of a wine from a certain appellation with a more or less defined set of characteristics. Part of what we do at Wine Secrets Barcelona is to hunt down wine that fits those criteria on behalf of an importer who will then submit it to the tender.

At 8:45 am I jumped into my Kia rental car at the Madrid Barajas airport and headed northwest towards Toro. It was my first time in this part of Spain and what first struck me was how different the landscape is compared the northeastern region of Catalonia, my home since 2002. Whereas the topography in Catalonia is highly varied, with everything from smooth beaches to rugged mountains, the highlands north and west of Madrid seem infinite with their undulating plains. I had been lucky with the weather, February is notoriously unpredictable here, and the bright blue sky was immense.

The Big Beautiful Skies North of Madrid

At mid-day I drove through the little town of Toro and crossed the Duero before I reached the vineyards of Estancia Piedra, half an hour down the charming country road. It’s an impressive place to visit for any wine aficionado, both in terms of the winemaking facilities and, especially, because of the absolutely stunning vineyards that surround them in true French chateau tradition. There’s nothing chateau about the cellar itself though. It’s simply a square building tucked into the landscape and designed for one sole purpose: making wine in the most efficient way possible while respecting the tremendous grape quality provided by the vineyards outside its walls. There is, however, an imposing mansion up on the hillside, overlooking the whole valley with vineyards on both sides of the little river that splits it. The locals, I was to learn later in the day, mockingly refer to it as Falcon Crest, a fitting name I think and not just because of how it looks. Also because of the apparent wealth of the owners of Estancia Piedra, who live most of the year in the Cayman Islands. In the mid 1990s, the current owners approached the head of the appellation of Toro to find out where the absolute best vineyards in the area could be found. Checkbook in hand, they secured a 40-hectare vineyard planted in 1968 with a density of 1,000 plants per hectare, all trained in gobelet. It is a truly awe-inspiring sight and enough to make any wine-lover’s jaw hang to their belt buckle.

Happiness Comes Easy in these Surroundings: 40 hectares of Vines Planted in 1968

The Sculptural Beauty of Old Vines

The Typical Sandy Soils of Toro; great Drainage and Insulation while Helping to Keep Plants Healty.

The general manager of Estancia Piedra is Gonzalo Sanz who comes from a long line of winemakers in the appellations of Toro and Rueda. Competent, experienced and to the point, Gonzalo showed me around both the vineyards and the cellar before we sat down to do what I was there for: to taste their wines and see if their profile would be a good match for my buyer in Sweden.

Barrel Room at Estancia Piedra

The wines of Estancia Piedra are clean, well balanced and structured. Everything sits where it should. It wasn’t always like that. Before Gonzalo took over the day-to-day running of the winery and started to capture the new owner’s ideas in a bottle, the wines from this bodega were classic Toro: big, bold and not much more. Now, there’s a fruity seductiveness to them that I really liked. As full-bodied as they are, they never feel heavy or overpowering. The oak has been relegated to the base of the wine and it never masks the varietal notes or muddles things up when you’re trying to sense the hallmark sandy soils of the Toro appellation. This is exactly what I’m thinking of when I talk about modern Spanish wines. It’s really quite simple: well-made wines that convey grape variety and place. Simple in concept, but not necessarily simple to achieve. Although the scale and budget of Estancia Piedra is beyond what most winemakers can dream about, they still take part in the quiet revolution that’s totally changing people’s perception of what Spanish wine is.

Stay tuned for part 2 where I wolf down some delicious, local foods before I visit the very cool wine making project of Kiko Calvo: Bigardo!

We’re Launching a New Wine in Norway!

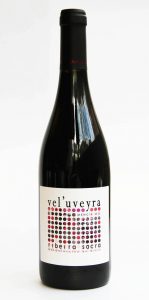

2019 couldn’t have gotten off to a better start. On January 11th, we’re launching a new wine for the Norwegian market: the deliciously juicy Vel’Uveyra from the Ribeira Sacra appellation. We are very excited about this launch!

The 2016 Vel’Uveyra hits the Norwegian Market

This is a great representative of what we like to call New Spanish Wine (#newspanishwine), where the vintner is looking to express grape variety and terroir and the influence of oak is relegated to the background.

Vel’Uveyra is made by Ronsel do Sil, a small family-run cellar located roughly an hour and a half east of Ourense. Vintner María José Yravedra is not only responsible for the winemaking, she is also the architect who designed the winery, discreetly integrated into the hillside and overlooking the meandering River Sil below.

Vel’Uveyra is a red wine made from the Mencía grape, commonly found in Galicia as well as in the adjacent appellation of Bierzo, further inland. The vines grow on very steeply sloped hillsides above the River Sil in soil composed of different types of granite. In fact, the terrain is so steep that the work in the vineyards in Ribeira Sacra is referred to as Viticultura Heróica (Heroic Viticulture). Harnesses are often required to safely work the land and, in many places, you see railings among the vines, allowing workers to move both equipment and grapes more safely and efficiently.

Heroic Viticulture in Ribeira Sacra

The grapes are harvested from several plots of land with vines ranging from 10 to 60 years old, growing at altitudes between 350 and 450 meters. The fermentation, using only indigenous yeasts takes place in a combination of 5,000-litre foudres and 2,500-litre steel tanks. Afterwards, the wine rests for approximately nine months in used 225-litre oak barrels.

The 2016 Vel’Uveyra is seductively fruity both on the nose and the palate. It has notes of blackberries, violets and underbrush. The wine feels very fresh and pleasant with a wonderful balance of almost creamy balsamic texture and a marked yet well-integrated acidity. The hallmark minerality of the region comes through, giving it structure. It’s a wine that has a lot to offer and is highly versatile when it comes to food pairings. I would especially recommend it for moderately heavy dishes with white meat or light game, mushrooms or root vegetables. It also pairs wonderfully with the fruity acidity of tomato, so bring on the pizza!

Harvesting in the Steep Hillsides above the River Sil

Vel’Uveyra Mencía 2016 will be available at the Norwegian Vinmonopolet from Friday, January 11th.

Joan d’Anguera and the Guts to Follow your Instincts

If you drive just over an hour south of Barcelona to the old vermouth capital of Reus and from there another 45 minutes west to the tiny village of Darmòs, you’ll find the small Joan d’Anguera winery. Belonging to the Montsant appellation, it has been in the Anguera family since 1820 and today is run by brothers Joan and Josep. You’d think that a winery that has been in the same family for two hundred years would be the epitome of stability with its ways set in stone. Actually, over the past eight or nine years everything has been questioned and shaken up at Cellers Joan d’Anguera. And that’s very exciting!

The Brothers Joan and Josep Anguera

Brothers Joan and Josep see themselves as farmers just as much as vintners. They have a profound connection to their land and they’re proud of that. They know who they are, where they come from and where they’re going. That last part took a while to crystalize in their minds, though. Up until 2012, they had been making solid, high-quality, Montsant-style wines: big and full-bodied, with plenty of fruit, color and oak. Wines that packed a punch! But the Anguera brothers were not excited about their own wines. They made these wines in auto-pilot mode, going through the motions of what was considered the right way to make wine in Montsant back then. The wines they made were excellent to many, including international wine critics who loved their muscular Garnachas and Syrahs. But that didn’t matter to Joan and Josep, because all they saw was the complete dissonance between the winemaking heritage of their forefathers and the wines that they were currently making. To them, this problem was so significant that it overshadowed any medals or Parker scores and made them uncertain about how to move forward.

Early Spring Colors at Joan d’Anguera. Vineyards are Ecologically Certified

As Joan and Josep were pondering these issues, a close friend of theirs, whose judgment they trusted, challenged them to aim higher in their winemaking. A lot higher. So they started tasting a lot of different wines to compare styles and get some serious parameters for their own wines. The wines their grandfather had made were always in the back of their minds: fine, elegant, persistent and highly drinkable. The culmination of this identity crisis led them to change virtually everything over the following four years. Production was slashed from 120,000 liters to about half that. They completely changed the way they age their wines, nearly eliminating the use of new oak barrels (only about 10% of barrels are now from new oak and many barrels are eight or ten years old). Cement tanks have become a very important vessel for them. When harvesting, the grapes reach the winemaking facilities within the hour of being picked. There, the bunches are fermented whole and then crushed by foot in the traditional manner inside the barrels. Hardly any sulfites are used. The grapes are organically grown and Demeter certified.

The Tasting Room is located right above the Winemaking Facilities

For Joan d’Anguera the road ahead is now well defined and the winery is very much an example of what is happening in Spanish wine in general. At Wine Secrets Barcelona we are very proud and excited to be representing Joan d’Anguera as we know that they will continue to make excellent wines in the years to come.

In Norway, the official importer for Joan d’Anguera is Oslo Wine Agency. Find more information on how to buy their wines here: https://www.oslowineagency.no/leverandor/joan-danguera

·

Esteve i Gibert – Passion over Money

Due to the work on my new winetasting space in central Barcelona, it had been weeks since my last outing to visit a winemaker and I was feeling the call of the vineyards. So, this last weekend I rounded up some friends and off we went!

Overlooking the Penedès Plains with the Storm Looming

Esteve i Gibert is a small, two-man operation just outside the little town of Subirats in the appellation of Penedès. Getting down there from Barcelona is quick and easy. I recommend taking the commuter train 45 minutes south to the Cava capital: Sant Sadurní d’Anoia. From there you can either take a cab or simply walk. The latter takes about an hour and it’s a bit of a climb, but still the better option in my book as the surroundings are beautiful and it gives you an idea of the lay of the land. Walking there will also help you work up an appetite and get your taste buds ready for some winetasting!

The Tasting Started Outdoors, but Quickly had to be Moved Inside

Albert López is the winemaker behind Celler Esteve i Gibert, which he owns with his father-in-law, Pep Esteve Gibert. The winery cultivates 19 hectares of land and the vast majority of the grapes are sold to other winemakers in the area (mainly to one prestigious cava maker) so they actually only farm about 3 hectares of grapes for their own wines. This yields just 15,000 bottles a year. The scale is, in fact, so small that vintner Albert López has to juggle winemaking with another job.

From Esteve i Gibert’s Treasured 90-year-old Macabeu Vineyard. Beautiful!

Given this situation, many in Albert’s shoes would opt to maximize the output of the 19 hectares and increase cashflow, but that’s not an option. Quite the contrary, Albert and Pep prioritize continuously improving on quality and, little by little, increasing the portion of land that goes to their own wines. These kinds of priorities take guts, patience and determination. When you add to the equation that there has been a severe drought the past few years (2018 has seen more precipitation), reducing the harvests even more, these guys deserve more than just a little respect. Plus, all viticulture is done according to ecologically sound standards and sulfites are kept to a bare minimum.

At the same time, Esteve i Gibert embodies a typical story in today’s Spanish viticulture: young enologists and agricultural engineers who take over old, sometimes abandoned, vineyards. They value and respect the traditions of the trade and the legacy of their forefathers, but are at the same time not afraid to experiment and refuse any straitjackets. This cocktail of know-how and energy, on one hand, and access to an abundance of old vines capable of producing grapes of exceptional quality, on the other, goes a long way towards explaining why Spain is possibly the most exciting winemaking country in the world today.

Winemaker Albert López in the Tasting Room

Esteve i Gibert mainly focuses on local, traditional grape varieties. Among the reds you’ll find the native variety Sumoll (see the previous blog post for more on this unique grape) as well as Merlot, which has been widely grown in the appellation for generations. The whites are dominated by two Penedès classics; the elegant Xarel·lo (scroll down to “The Xarel·lo Summit” for more) and the more intense Macabeu. Plus other grape types such as Albariño, Malvasia de Sitges and Sumoll Blanc. Fans of powerful, full-bodied reds will get their fix with the l’Antana whereas lovers of elegance will adore Les Vistes. Modern additions to the catalogue include two delicious sparkling wines made with the ancestral method (single fermentation, not double like cava or champagne).

If you’re interested in visiting this other winemakers or in organizing a winetasting at Wine Secrets Barcelona’s beautiful space in central Barcelona, don’t hesitate to get in touch with us via mail or social media

·

Sumoll, back from the brink of death!

There are roughly 240 known grape types currently used for wine making in Spain. Many of these are rarely seen whereas a much smaller number we see all the time. Winemakers tend to steer away from the less productive grape varieties or the ones that present major challenges in cultivation. And of course, there’s the fact that some grapes have just become more popular with consumers who easily fall into the habit of juggling two or three grape names when they shop for wine or visit a restaurant.

Approaching Montrubí for Another Rough Day of Wine Tasting

One of the many positive consequences of the revolution that’s been taking place – and that’s still very much going on – in Spanish wine making the past 25 years or so, is the recovery of autoctonous grape types that had fallen into disuse. Quite often now I get the chance to taste a wine made from a grape variety that I’d never heard of, something that I think is really fun and interesting because it makes opening a bottle of wine even more of a moment of anticipation. Its almost always the result of a small farmer’s hard efforts in bringing back to the market a piece of local viticultural history. Varieties that used to be available, but then for the reasons mentioned above, were pushed aside and quite literally torn out of the ground to give way to more productive and more popular grapes. These rediscovered grapes form an intrinsical part of a region’s winemaking tradition and its sad to see that disappear and conversely, a great joy to see someone fight to keep it alive and give wine lovers the chance to get to know this new, yet old, grape type.

Sumoll is a red grape with it’s origins in the appelation of Penedès, just an hour’s drive south of Barcelona. While it is quite productive, its also difficult to cultivate for quality winemaking purposes because the fruit have a tendency to mature unevenly. Within the same cluster you’ll commonly find grapes that are quite ripe next to green ones. This of course brings the issue of grape selection to the forefront of the vintner’s concerns although increasingly some deliberately leave unripe grapes in, seeking a more rustic profile for the final wine.

Tasting the Radical 2017 among the Vineyards that Yielded it.

Up until the 1980s there were plenty of Sumoll in Penedès, but two main factors were to dramatically change that. First, the needs of the cava industry led non-winemaking farmers to yank up their Sumoll vines and instead plant Xarel.lo, Parellada and Macabeu, the three grapes traditionally used in cava. Secondly, the very characteristics of wines made from Sumoll made it a less popular grape among wine drinkers. Back in the eighties people wanted big, bold and muscular reds with as much color as possible. Wines you could eat with a knife and fork, preferably. Sumolls have a hue reminiscent of those made from Pinot Noir; lighter and more delicate. Fortunately, another common trait between Pinot Noir and Sumoll is a persistance in taste. The lack of a deep color fools you, if you will. Rich in lively, red fruit notes that take on deeper and darker ones with ageing, the younger ones often display fresh and agreeable citrus flavors (tangerine). It has good acidity, gives a medium to high alcohol content and marked tannins. In other words, the potential for ageing is very good. I’ve tasted 15-year-old wines from the grape that were excellent and with years ahead of them still.

Currently Sumoll is booming and that’s great news for any wine aficionado! Vintners like Montrubí, Pardas, Esteve i Gibert, Bodegas Puiggròs and quite a few others make great reds from it. Even big, industrial wine producers are jumping on the band wagon. This past Monday, Wine Secrets Barcelona was invited to a masterclass on Sumoll at smallish winemakers Montrubí in Avellá, in the inner highlands of Penedès. Winemaker Josep Queralt showed us the vines, explained the characteristics of the soil (chalky clay mostly, with one vineyard very rich in black slate) before we tasted samples from various vessels that they experiment with (cement eggs, steel tanks, clay amphorae, oak barrels and foudres). Finally, we tasted our way through all the wines that they make from the Sumoll grape; some six reds, a rosé, a sparkling rosé and a dessert wine. A very instructive and special experience that, once again, made me appreciate my job!

Winemaker Josep Queralt of Montrubí Explaining the Sumoll Variety

The Cement Eggs are Proving to be an Excellent Vessel for Ageing

I strongly recommend that you make a little effort to locate a couple of different wines made from the Sumoll grape. If you like to leave the beaten track every once in a while, you’ll be handsomely rewarded!

(If you’d like specific recommendations on wines or winemakers, don’t hesitate to drop me a line via mail, Instagram, Facebook or LinkedIn. Salut!)

·

The Xarel.lo Summit

On the last Monday of June for the past four years I’ve had the privilege of attending an outdoor wine event that is nothing short of unique, La Cimera del Xarel·lo, quite literally: The Xarel·lo Summit. This wine fair has two main stars: its location and the grape varietal it celebrates.

Few Wine Tastings can Compete with this

Have you ever seen one of these beautifully inaccessible old chapels, perched on the very top of a mountain? The Ermita de Santa Maria de Foix is exactly that. Commanding stunning 360-degree views over the villages and wine fields below, with the Mediterranean Sea to the east and the implausibly shaped Montserrat mountains to the west, it’s a captivating place that beckons tranquility and pause. Xarel·lo is the white grape of Catalonia. It’s a varietal that combines subtlety, elegance and longevity. It seems that this event could not be held anywhere else. So, for those who don’t know, Xarel·lo is a grape type that for generations was almost exclusively used for producing Cava, Spain’s most important sparkling wine. Little by little, some wine makers started making still white wine from Xarel·lo and quickly saw that its potential went way beyond table and bulk wine. Xarel·lo has a set of characteristics that places it firmly in the upper echelons of the grape hierarchy. Balancing good acidity and a relatively high level of alcohol, it provides excellent ageing potential. Citrus and sharpness in younger wines. Fruit on the more tropical side, but contained and elegant, never vulgar, in wines with some age. The Penedès is its natural habitat and, given the soil there, a mineral component is often found in the wines, giving them a backbone that, paired with the mentioned pH-level and alcoholic content, provides the intrepid wine maker with the ingredients for some seriously interesting wine making.

Xarel.lo Offers a Wonderful Variety of Style

La Cimera del Xarel·lo has been growing steadily and in this fourth edition almost 100 different wines, all made from the Xarel·lo grape, were presented by some 30 wine makers, ranging from the small, one-person garage projects to medium-sized producers who make about half a million bottles a year.

Hard to Choose a Favorite in this Field!

This year I was fortunate enough to get invited to a special, one-off wine tasting held by renowned wine journalist Ramon Francàs. With a 10-bottle line-up of hard, if not impossible, to find wines it was a tasting that went a long way to show the wonderful potential and reality of the Xarel·lo grape. Among the highlights were the 2013 Nun Vinya dels Taus, the 2004 Electio and the 2008 Xarel·lo Pairal from Can Ràfols. Absolutely impressive wines! A special mention also for the cava Turó d’en Mota 2001 from Recaredo, which had been disgorged only three days before and in spite of this showed a depth and richness of nuance that I rarely come across. A major wine!

·

The Amazing Vinoble Fair

I just participated in my first Vinoble. For those unfamiliar with this wine fair, it’s the preeminent professional gathering in the world of sherry. It’s held every other year in the beautiful town of Jerez de la Frontera, one hour straight down the road from Seville, in southwestern Spain. And it’s an event that any self-respecting sherry-lover dreams about.

Prior to attending Vinoble, I certainly didn’t consider myself a bona fide sherry-lover. I was more of an occasional yet mostly ignorant consumer, having had some very memorable experiences and some great food pairings with a fino or amontillado, but I honestly knew very little about this Andalusian fortified wine. My ignorance didn’t come from a lack of desire to taste and discover. If my knowledge of sherry was superficial at best it was simply due to the fact that I hadn’t been around it much. And that may be precisely the main obstacle to sherry achieving widespread popularity: people don’t really know what it is because its consumption is so limited, geographically speaking. In Seville, Malaga and other cities in Andalusia, sherries are widely available and consumed. Any hole-in-the-wall bar will have a dozen types. But you don’t have to travel far for that to change completely. In culinarily cosmopolitan Barcelona even well-stocked bars are highly unlikely to have any sherry that is even remotely interesting. A shame, indeed. So, I decided to go to the holy grail of sherry fests to taste, ask questions and learn!

Jerez de la Frontera is only an hour-and-forty-five-minute flight from Barcelona, but as I sat in the back of the cab that took me to my hotel it was like I’d landed in a different country. It sounds cliché, but the landscape truly is different; people dress differently, their tone is different and, as I soon learned, what’s in their glass is different, too. I was excited!

Winemaking in this region dates back some 3,000 years, to the Phoenicians. Since then, the Romans, Arabs and then the Christians have been running around, doing their thing, all contributing to what is an exceptionally rich culture. Jerez de la Frontera abounds with old money and southern charms. There’s wonderful architecture throughout the center of town and it’s a very pleasurable place to spend some time. For the gastronomically obsessed like myself, it’s full of places to graze or go completely overboard. I seemed to just naturally gravitate towards to the tabancos, traditional places where the locals nibble on jamón and sip a chilled fino.

The fair was a resounding success and a true privilege to visit. Extremely well organized in an intimate setting in and around the romantically beautiful old palace of El Alcázar (which also boasts archeological findings dating back 5,000 years) sitting on a hilltop overlooking the town. Hard to beat.

Over the three days I was in Jerez de la Frontera, I tasted some 140 different sherries and participated in courses and visits to sherry-makers in the area. I learned a lot and have already begun to dig deeper, taste more and play around with different food pairings. Sherry is very much a world of its own within the universe of wine. The range goes from bone dry to very sweet, though most types of sherry are on the drier end of the spectrum.

Starting very soon, in our new space, Wine Secrets Barcelona will begin offering tastings with or without food pairings so more people get the chance to discover the wonderful world of sherry. So, get in touch and find out what we have to offer!

Careful though; scratch the surface and you might get hooked for life.

·

Hunting for Wine in Galicia

The amazing increase in the variety and quality of Spanish wine over the past generation can be seen – and tasted – all over the country. At the very forefront of this incredibly exciting development is the region of Galicia. Located in the upper left corner of the peninsula, Galicia has traditionally been associated with white wines, especially the ones made from the Albariño grape. But it’s the Galician reds that have become the game changers, turning people’s perception of Spanish red wine on its head.

The red wines in Galicia are made from many different grape varieties, the most well-known perhaps being Mencía, also abundant in the appellation D.O. Bierzo, but Caíño, Brancellao, Garnacha Tintorera, Grao Negro, Sousón and Mouratón are all used to varying degrees. These Atlantic reds are cooler and lighter in style than their counterparts from inland Spain, where the warmer weather drives up the alcohol content. Galician reds are often feminine, fresh and elegant, but their more delicate style does not by any means translate into a lack of character. Quite the contrary, well-made reds from the region are persistent in taste and make you want to pour yourself that second or third glass. Also, they are incredibly versatile, combining very well with a wide range of dishes and lending themselves to being enjoyed year-round. YES, I love Galician reds!

Last week I boarded a plane in Barcelona and headed for Vigo, a not-very-attractive port city just north of the Portuguese border. My mission: to go hunting for delicious red wines on behalf of Scandinavian wine importers. Some of the wines, the cream of the crop, also end up in Wine Secrets Barcelona’s ever-expanding cellar. So, if you and a bunch of your co-workers or friends want to treat yourself to some liquid glory, you know what to do. The most important thing for me when I go wine hunting for an importer is to have a very clear idea of what the buyer needs. Once I have that defined, I get into my rental car and brazenly set off into wine country. The car in this case was an eggplant-colored Fiat 500, sunroof and all. I’m 1.91 m, 96 kg, bald and bearded, but to my surprise the little Fiat proved to be quite comfy, although the hipster factor was bordering on the ridiculous.

A Proper Hipster Mobile for my Galician Wine Adventures

I spent the next five days in and around the D.O.s of Valdeorras, Ribeira Sacra and Rías Baixas. I love my job and an absolute highlight of it is being able to stand in a beautiful vineyard talking with the winemaker and understanding the philosophy behind the wines that they make. It’s a humbling experience listening to someone who puts everything they have into working the vineyard from a place of respect for the land and the environment, treating each and every plant in the best possible way and realizing that he or she is merely a caretaker, seeking to yield the very best grapes possible and then turn them into something magical.

A Norwegian Roaming the Hillsides of Val de Sil

The world of wine, at least in this lower-volume realm of it, often has that mix of the romantic and the beautiful, but also the component of hard reality. Because nature is always there to send down a pummeling hail storm right before harvest should you get too cocky. Perhaps that’s why there’s such camaraderie and open arms between strangers who share the same profession. That week I was welcomed into the vineyards, bodegas and homes of winemakers from Vilamartin and O Rua in Valdeorras, via Manzaneda up in the mountains above, through the breathtakingly gorgeous Valle del Sil in Ribeira Sacra and the lush, almost tropical green gardens and tranquil rivers of Rías Baixas. It was a privilege to share some time with each and every one of these viticultores.

¡¡MUCHAS GRACIAS … MOITAS GRAZAS!